In Hole in the Stone (Summer 1995, Vol. 6, Iss. 4), singer Alix Baillie shared her unique perspective on Sacred Harp singing in an article titled Down-Home Singing Frenzies: Sacred Harp for Pagans. Though Baillie comes from a Pagan background, she found herself captivated by the raw, communal power of Sacred Harp. Her story serves as a beautiful reminder of the unwritten rule in Sacred Harp singing: “Leave your politics and religion at the door.”

Although Sacred Harp is deeply rooted in the Christian tradition, Baillie reflected on how warmly the community welcomed her, despite her different spiritual background. She emphasized how the power of the music, the open harmonies, and the shared tradition of singing together transcended any differences. While some Christian singers might have been puzzled had they known about her spiritual beliefs, Baillie discovered a space where music brought everyone together.

She described how Sacred Harp singers “live out” the love and unity that many faiths aspire to, focusing on the singing instead of theological differences. Baillie’s experience is a testament to the Sacred Harp tradition of inclusivity: while the lyrics may be overtly Christian, the power of the music transcends belief systems.

As Baillie’s story illustrates, Sacred Harp is best when it welcomes all singers with an open heart. The community thrives because we put aside differences and unite in song. You can find Alix Baillie’s name listed in the Sacred Harp “Minutes” around that time, a testament to her participation in this vibrant tradition.

–Kevin Isaac

P.S. It’s worth noting that Alix Baillie’s article was written nearly 30 years ago, and her views or perspectives may have changed since then. However, the piece offers an interesting snapshot of one enthusiastic singer’s attempt to bring her unconventional musical passion to an unconventional audience—an audience that might not otherwise have been open to reading about Christian hymnody. Baillie’s experience reflects the inclusivity and welcoming spirit that continues to be a hallmark of Sacred Harp singing, even as our community evolves.

Down-Home Singing Frenzies: Sacred Harp for Pagans

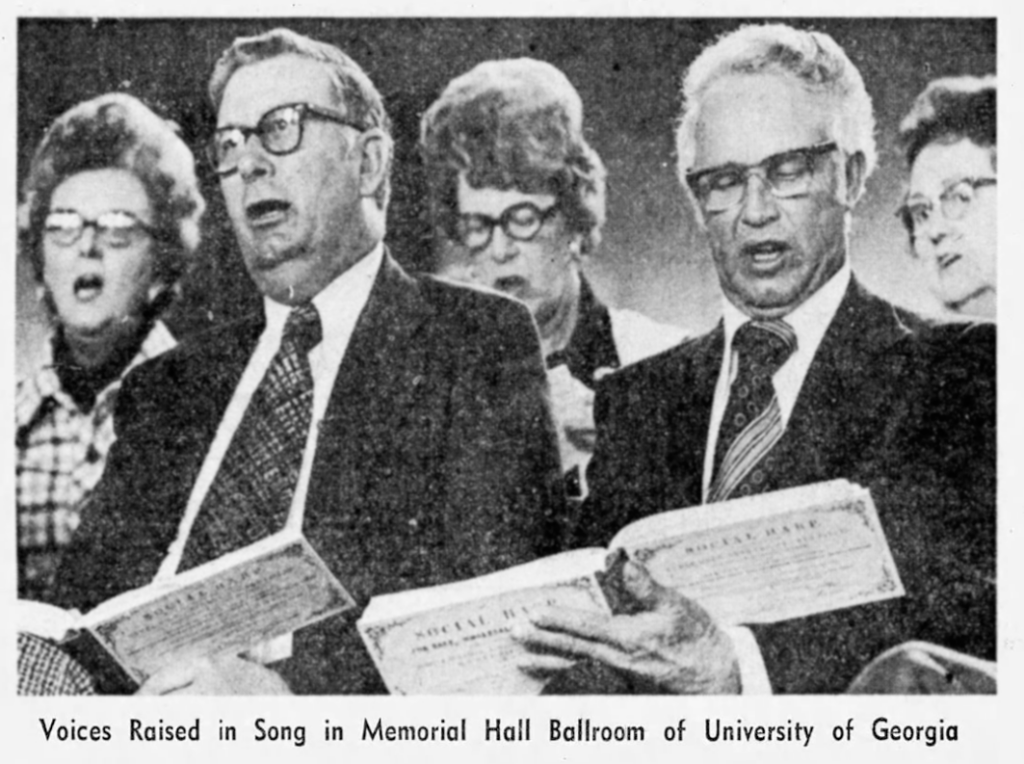

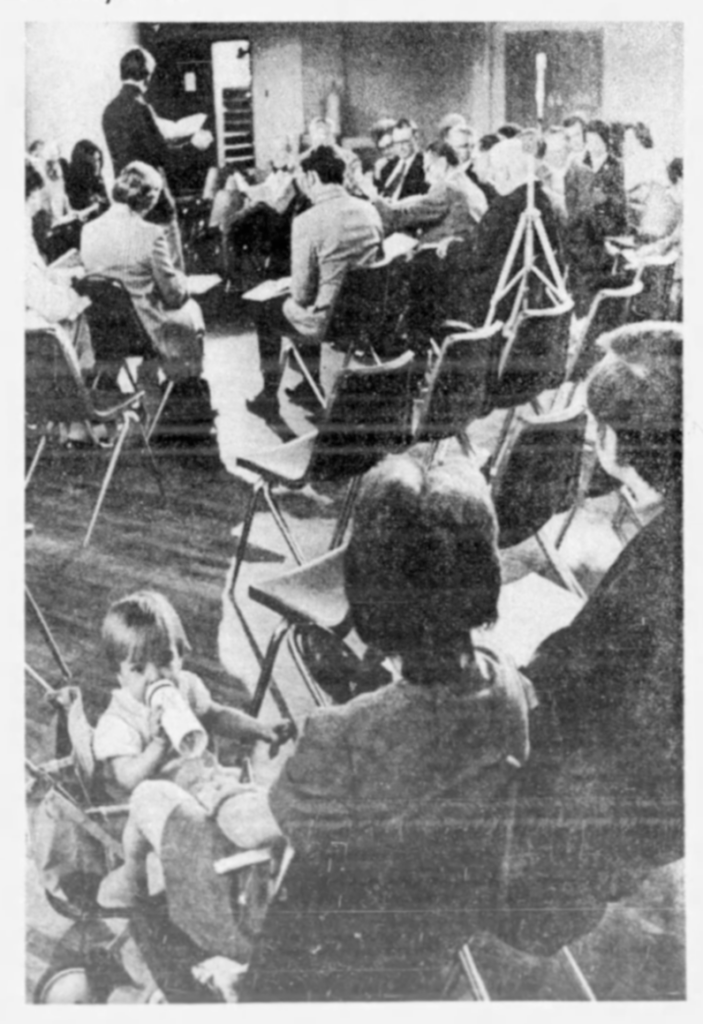

The sound whirls in the center of the room with the roar of a funnel cloud. Hundreds of voices — clear, rumbling, nasal — join in powerful harmonies, swept along over an inexorable, throbbing pulse. An outdoor ritual? No, a Sacred Harp convention. The singers seat themselves, not in a circle, but in the “hollow square,” facing each other in voice sections. They are singing from a book whose tradition has been carried on in these meetings since 1844, and which belongs to an even longer tradition reaching back to the eighteenth century. The book is The Sacred Harp, and even though the words are about Jesus, the music is, in the words of one Pagan visitor, “way too good for the Christians to have all to themselves.”

As it turns out, the Christians don’t have it all to themselves. I recently posted a query on an Internet list, asking non-Christians how they felt about singing The Sacred Harp’s texts, and asking Christians how they felt about non-Christians participating. The response from both groups was quite positive. I heard from Unitarians, Jews, agnostics, atheists, people who are a bit of everything, people who were nothing in particular. A woman in Eugene, Oregon, who identified herself as an atheist, reported that some folks up there substitute Goddess for God. At the opposite end of the spectrum, a woman who describes herself as a traditional Roman Catholic uses The Sacred Harp’s hymns in her private devotions. Many of the respondents were people who feel alienated from their Christian upbringing, but find community, spiritual satisfaction, and a connection to the past in Sacred Harp singing.

The connection to the past is very real, and is reiterated at every Sacred Harp convention. At some point, usually just before the midday dinner, one or two singers read aloud the names of singers who have died in the past year. One of the readers, usually an elder in the Sacred Harp community, gives a talk about death — that it waits for all of us, but that it is nothing to fear. Although this is all in a Christian context, the emphasis is not on platitudes like “they’re all with Jesus now,” but rather on the continuity of death and life. In one sense, the dead singers — all the dead singers, for countless generations — live on as we invoke their memory and sing the songs they loved. Stress is also laid on the fact that everyone sitting in the room will pass through the Veil someday. This is not grim, but joyous: not only will we be remembered in our turn, but we’ll be able to sing together endlessly in the biggest convention of them all on the other side.

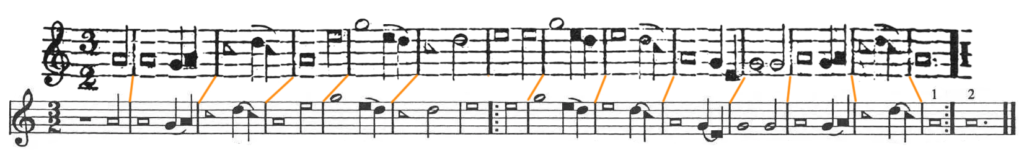

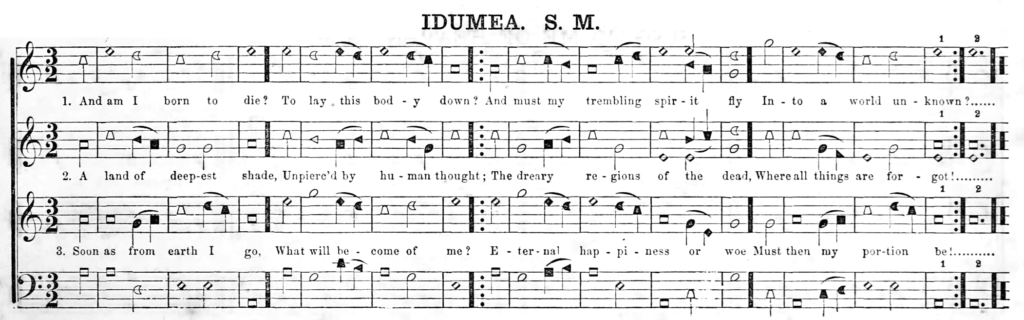

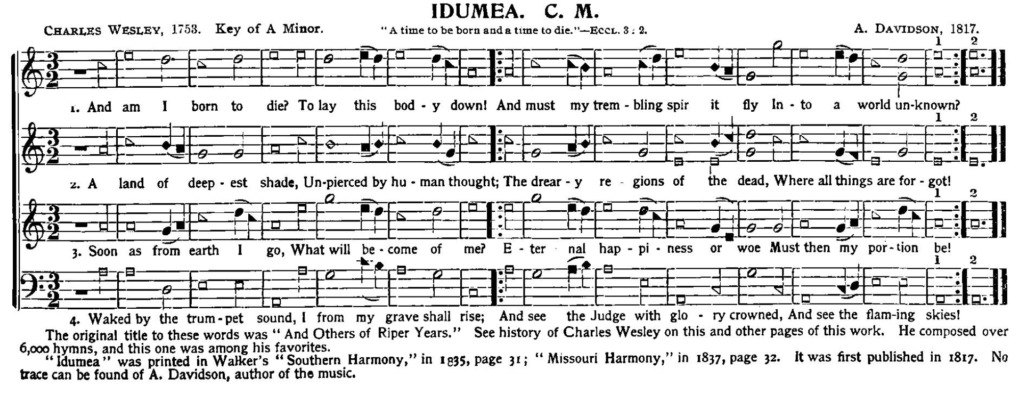

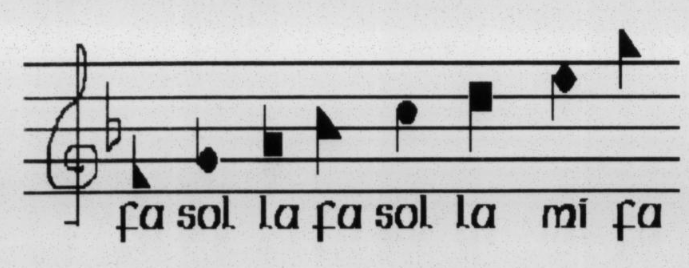

Many of the songs in The Sacred Harp and the traditions that accompany them, go back to colonial New England. They flourished in the singing schools advocated by Rev. Thomas Symmes in the 1720s as a remedy against the sad state of rote-learned church music. Typically, a singing master would set up in a church or tavern for a week or two and hold daily classes for adults and children. He would charge a nominal fee for the lessons, and make most of his money from the sale of his particular songbook/textbook. He would teach the rudiments of music using the old four-syllable English solfege: FA, SOL, LA, MI. The students would learn the unaccompanied polyphonic music first, part by part, then put the parts together. At the end of the school, the community would have a core of good sight-singers, and the singing master would move on to the next town.

The appeal of the singing schools was not strictly musical. In strait-laced New England, the singing school provided a parentally-approved way for young people to flirt. Musicologist Irving Lowens cites a 1782 letter written by a Yale undergraduate: “I am almost sick of the World & were it not for the Hopes of going to singing-meeting tonight & indulging myself a little in some of the carnal Delights of the Flesh, such as kissing, squeezing &c &c I would willingly leave it now.” The singing school, and the periodic singing-meetings that succeeded it in some places, also provided an enjoyable way for scattered rural families to socialize. The idea of gathering from far-flung parts for a day of meeting, eating, and singing continues today in the tradition of all day singing and dinner on the grounds.

The New England singing-school phenomenon peaked in the 1770s and 1780s. The Yankee composers/singing masters all had other trades and were usually self-taught in music. Their tunes are modal, powerful, and expressive — and ignore the rules of “correct” counterpoint and harmony. Besides plain tunes, in which all the parts move together, they wrote so-called fuguing tunes. These are not formal fugues, but have sections where the voices enter separately, in melodic imitation. William Billings, in the preface to his Continental Harmony, gives the best description yet of a fuguing tune: “Now the solemn bass demands [the listener’s] attention, now the manly tenor, now the lofty counter, now the volatile treble, now here, now there, now here again. — O enchanting! O ecstatic!”

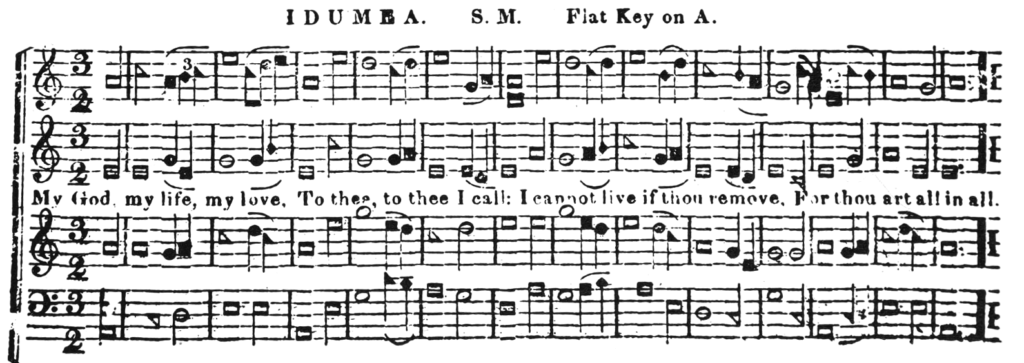

The wild harmonies and exuberant expression of the Yankee singing-school music gradually lost favor in New England. Churches acquired organs, and Lowell Mason and the “better music boys” sought to “improve” American music by replacing it with watered-down European art-music. As singing masters began to move west and south at the turn of the nineteenth century, the first tunebook in shape notes appeared, William Little and William Smith’s Easy Instructor. Earlier teachers had tried various means of representing the solfege syllables visually, but Little and Smith’s system proved the best; it is still used in The Sacred Harp. Each syllable has a unique shape:

Without worrying about keys, a singer can learn to sight-read quickly.

This effective new tool was taken up in the South. In 1815, Ananias Davisson published his Kentucky Harmony in the Shenandoah Valley. This book marked a turning-point in singing-school music: Davisson put some of the most popular songs from round-note Yankee books into four-shape notation, and added new compositions in a Southern-folk idiom. Davisson and other Southern composers wrote new tunes in the folk idiom and adapted ballads and dance-tunes to hymn texts. Their arrangements, too, were folksy, sometimes more like the English-folk sound of the Yankees, sometimes like bluegrass. Although this vigorous unaccompanied singing was born in New England, it was nurtured and carried into the present in the South.

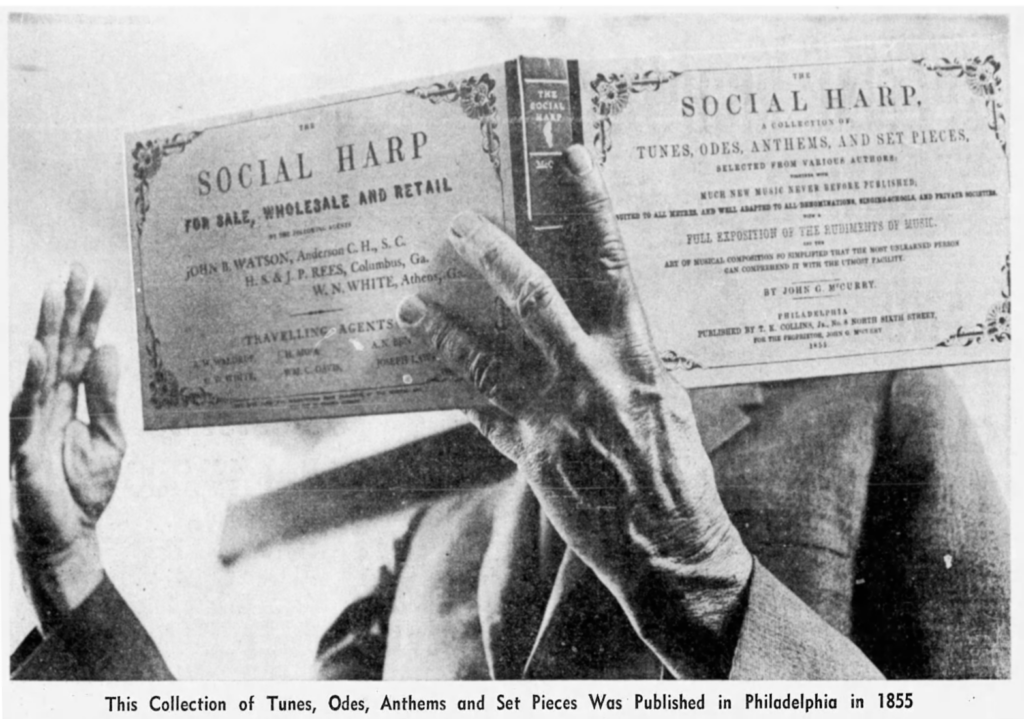

B.F. White and E.J. King’s Sacred Harp, first published in 1844, was one of the last four-shape tunebooks; by the 1850s the tide had turned to seven-syllable solfege (the modern DO RE MI) with seven shapes. Most tunebook publishers changed with the times; along with the new notation came sweeter harmonies and gospel-music influences. The Sacred Harp, however, kept to its traditions of four-shape notation, raw open-fifth harmonies, and Anglo-American tunes. Some efforts were made to update the book. B.F. White’s son edited a revision in 1909 which included several tunes reworked into “correct” harmony. The free-ranging countermelodies were brought into close harmony positions and made to function as chordal harmony parts, losing their own melodic interest. Needless to say, this book did not find much welcome in the Sacred Harp community.

The more successful revisions have kept B.F. White’s underlying principles, but added new songs in the old style with each edition. One update that still raises controversy among arch-purists is the addition, in the 1911 James Revision, of alto parts to most of the old three-part songs. Some claim this addition softens the harmony too much by filling in the thirds of the chords — but anyone who’s ever heard a good paint-peeling Southern alto can testify there’s nothing softening about the alto part.

The current (1991) revision of The Sacred Harp includes works from the earliest Yankee singing masters, works by living composers, and pieces from every generation in between. Convention customs, too, go back to the colonial singing schools. At modern Sacred Harp singings, the group of singers is called the class; each leader in turn stands in the center of the hollow square to lead a lesson. The procedure is completely democratic: anyone at the singing can lead any song, provided it hasn’t already been sung, or used, that day. The arranging committee tries to make sure that everyone who wants to lead gets a chance. As each leader gets up, s/he calls out a page number. The leader or a designated pitcher finds a workable tonic pitch (hardly ever the actual printed pitch); each section finds its starting pitch from this. Then the whole class launches into the cacophony of singing the notes — everyone sings hir own part with the solfege syllables. Finally, the leader calls out the verses s/he wants, and the whole class sings, washing the leader and each other in waves of glorious sound, beating time with their hands and tapping their feet. At midday, they feed each other, in the potluck feast modestly called dinner on the grounds (from the tradition of picnic tables set up on the grounds of tiny country churches).

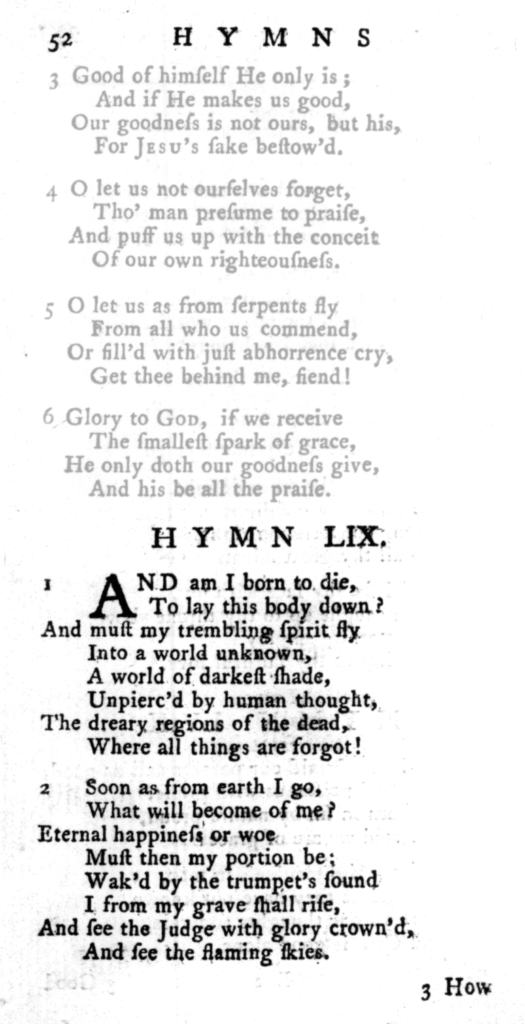

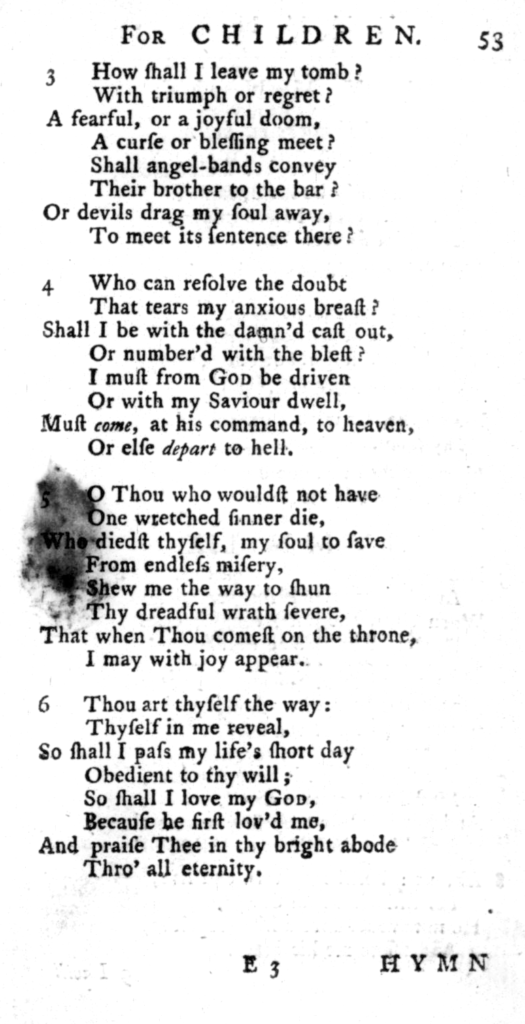

The texts Sacred Harpers sing all day are about Jesus and his God, but these are not the wimpy lyrics of standard church hymnals, nor are they as exclusively Christian as might appear. The texts are filled with death; life was harsh for the people among whom the shape-note books flourished originally. The God portrayed in many songs is a raging Old Testament God; the raw power of the Divine-in-Nature and of Nature Herself is feared and celebrated. Some of the songs are gentle and comforting, but in a sincere, not sappy, way. It is this directness of expression that seems to appeal to both Christians and non-Christians. One Christian woman wrote me:

“The words are specific, strong, and even offensive to some, but that is part of their power. …The faith expressed in the Sacred Harp is a specific faith believed by a specific group of people. …Their faith had depth because it was a specific experiential faith. …maybe Sacred Harp people respect this faith because they already know that experience means more than abstract theory.”

I heard similar expressions from non-Christians trying to describe the power of Sacred Harp. For me, the power of the sound itself, the psychic force of dozens or hundreds of people singing together, the absolute acceptance of anyone who joins the hollow square — in perfect love and perfect trust — far outweigh the disagreements I have with the specific theology of the texts. Georgian Richard F. Whatley recently posted an article called “Celestial Fruits on Earthly Ground” to the Internet list, in which he remarks that the single most impressive thing about the huge Midwest Convention is the number of different religions gathered under one roof. “Sacred Harp has a way of attracting people from all the spiritual walks who are willing to put their differences on the back burner; people who expect a miracle and come prepared to let it happen.” He concludes: “Where two religious sects are gathered in His (sic) name is called a war; where 20 are gathered is called a Sacred Harp convention.”

The Crone-like lyrics and earthly harmonies made me want to tell Pagans about Sacred Harp a year ago. I’m glad I waited, though, because in that year I’ve learned that the real magic of Sacred Harp is its community — people who actually live out the unconditional love most religions merely hold up as an ideal. The Sacred Harp has Christian words, but if you visit with an open, respectful attitude, you will be welcomed as an old friend. You may even find something you can adapt!

RESOURCES

- The Sacred Harp. 1991 Revision. Bremen, GA: 1991. Available ($13 postpaid) from Sacred Harp Publishing Co., 1010 Waddell St., Bremen, GA 30110.

- Cobb, Buell E., Jr. The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1978; paperback, 1989.

The best introduction to Sacred Harp history and culture. This is available directly from Mr. Cobb; I have his address somewhere. - Davisson, Ananias. Kentucky Harmony or, A choice collection of Psalm tunes, hymns, and anthems, in three parts. Ananias Davisson, 1815.

Facsimile edition, 1976, Augsburg Publishing House, Minneapolis, Minn. - Jackson, George Pullen. White Spirituals in the Southern Uplands. N.p.: The University of North Carolina Press, 1933. Reprint, with an introduction by Don Yoder, Hatboro, PA: Folklore Associates, 1964.

The first scholarly notice taken of shape-note music; deeper history than Cobb. - Lowens, Irving. Music and Musicians in Early America. New York: W. W. Norton, 1964.

Includes essays on New England school and the invention of shape-notes. - Directory and Minutes of Sacred Harp Singings.

Published annually by the Sacred Harp Publishing Company. Lists all Denson-Revision annual conventions and some smaller singings, including:- Rocky Mountain Sacred Harp Convention, third Sunday of September and Saturday before, Fort Collins. Contact John Ramsey, 303-221-9589 for more info on the convention and singings in CO/WY/NM. There are monthly singings in Fort Collins, Denver; probably elsewhere as well.