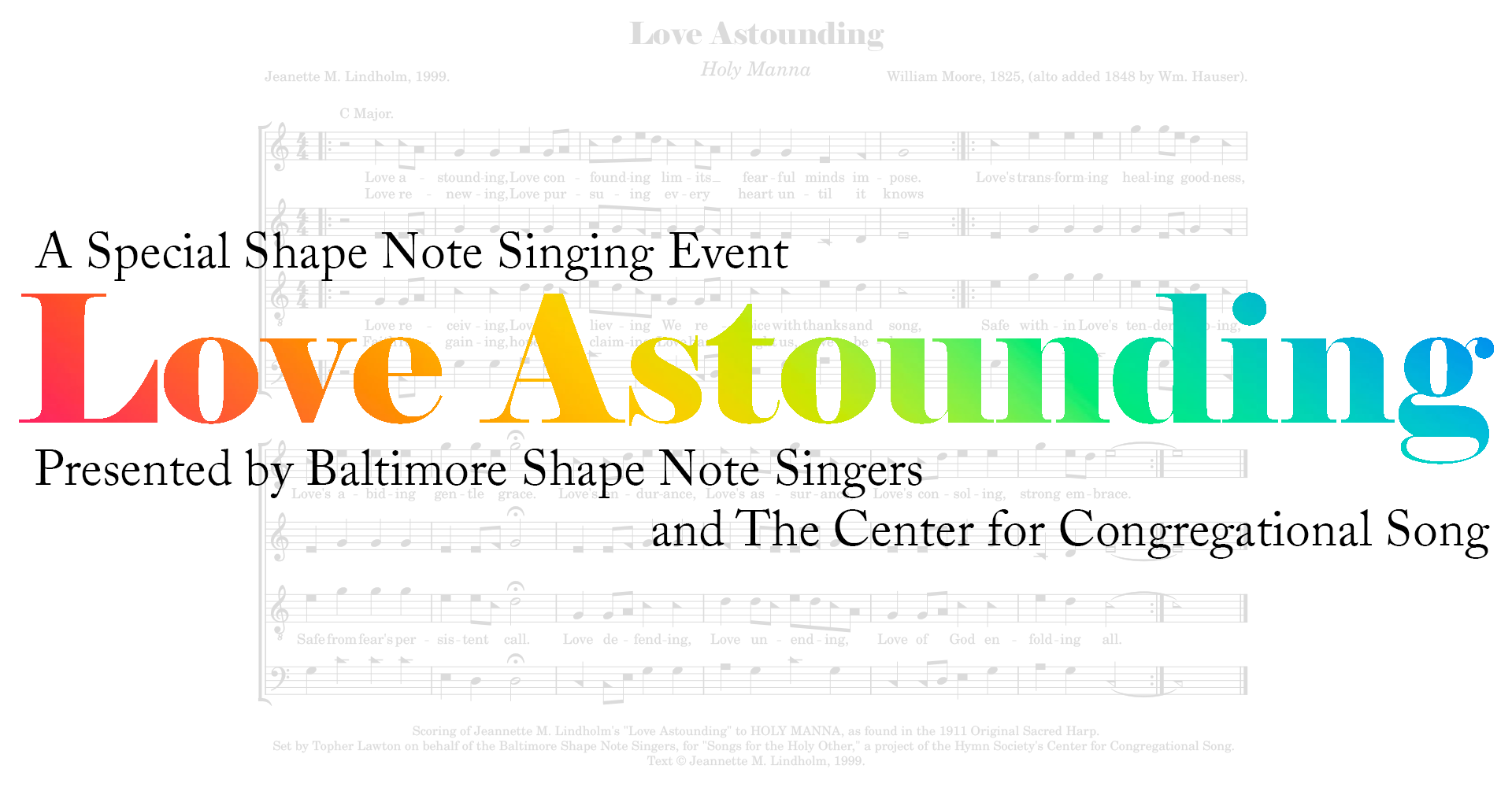

Presented by Baltimore Shape Note Singers and The Center for Congregational Song

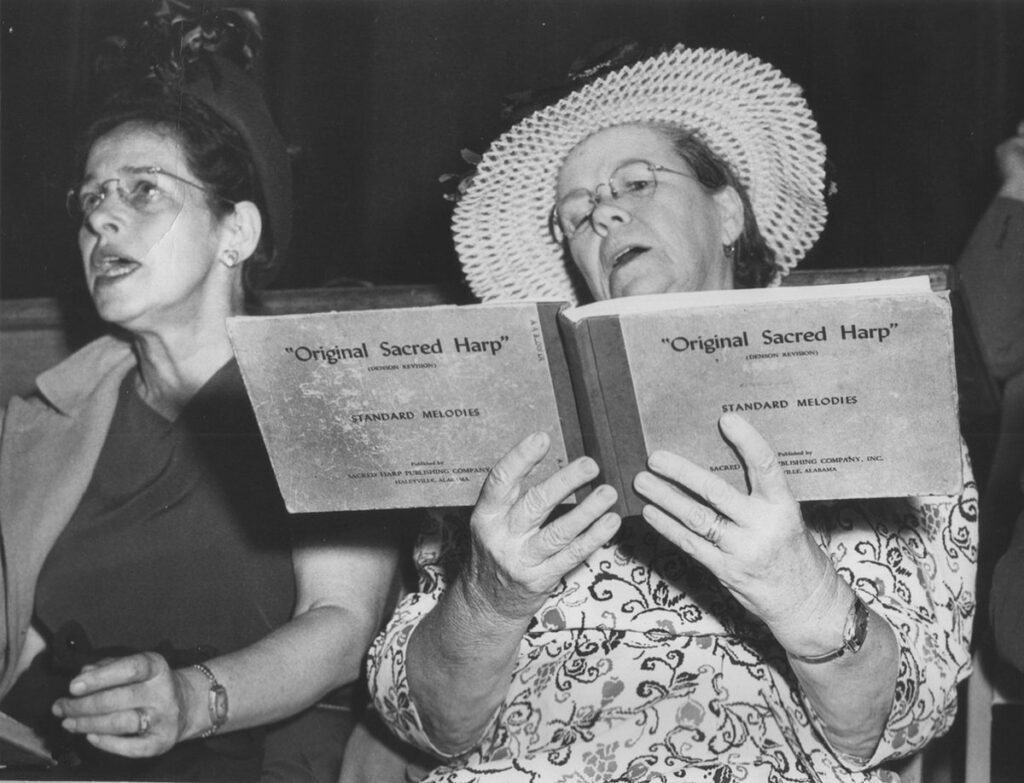

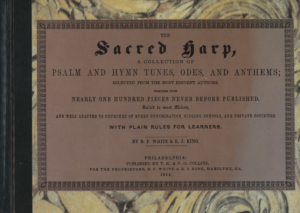

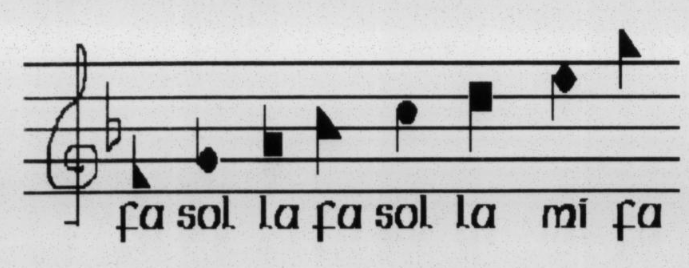

On Monday, January 13, 2025, the Baltimore Shape Note Singers met at Four Hour Day Lutherie for an evening that combined tradition with a focus on inclusion. The group sang “Love Astounding”, a poem by Jeanette M. Lindholm set to the tune “Holy Manna” from The Sacred Harp. This performance was part of the Songs for the Holy Other: Hymns Affirming the LGBTQIA2S+ Community project, recorded in the traditional Sacred Harp style.

A Typical Start

The evening began with the group’s regular Second Monday singing. About 22 singers attended, including a couple of first-timers exploring shape-note music for the first time. The first hour featured selections from The Sacred Harp and The Shenandoah Harmony, as is usual for these gatherings.

Before the break, Brian Hehn of the Hymn Society shared some background on the Songs for the Holy Other project, explaining its origins and purpose. Afterward, the singers took a short recess.

“Love Astounding”

Following the break, the group turned its attention to “Love Astounding”. Kevin introduced the song, while Lindsey guided the group through the notes to make sure everyone was comfortable. The song was sung three times before the group returned to their tunebooks to close out the evening.

A Collaborative Effort

The recording of “Love Astounding” is part of a broader initiative by the Hymn Society, which plans to release a series of videos for the project. Details on the release date for this particular recording aren’t yet available, but updates will be shared when more information comes in.

Thanks to the Community

A note of appreciation goes to Topher Lawton for scoring the tune. Special thanks to Nora, Sarah, Elizabeth, Kelly, Beth, River, Niamh, Samuel, Robin, Brian, Topher, Luke, El, Taylor, Cori, Katie, and Becca for bringing their voices to this event. Events like this reflect the role shape-note singing can play in bringing people together while expanding the repertoire to include works that resonate with modern audiences.

For those in the Baltimore area, the group welcomes anyone interested in exploring this unique and communal form of singing.

For more information, visit:

https://www.baltimoreshapenote.org/

https://thehymnsociety.org/resources/songs-for-the-holy-other/